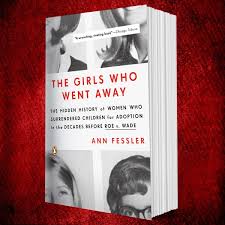

At the suggestion of a recently discovered blood relative, I read the book, “The Girls Who Went Away” by Ann Fessler. It gave me a different perspective on adoption from the birth mother’s point of view. As an adoptee, it also helped me further commiserate with what a traumatic experience this was for a 17-year old girl in 1951. The post-war boom made neighborhood status a very competitive and protective asset. If a young girl got pregnant, it somehow reflected more on “what the neighbors thought?” than on the welfare of their daughter. It was both embarrassing to their role of parents and a threat to their place in the community and even the workplace. Understanding this intense societal pressure is the key to why unmarried, pregnant girls were banished by their families and secretly sent away to deal with “their problem.

Although sex education was never discussed at home, it was also difficult for parents of this era to understand how a “good” girl could ever find herself pregnant. Where had they gone wrong? Since abortion was illegal and “single mother’s couldn’t possibly raise a child on their own,” adoption was really the only option. The thinking was that these “immoral” women would only destroy the child’s life, as they would be labeled “bastards on the playground.” As a result, parents would cruelly make their pregnant daughters hide until they could eventually send them away to a home for unwed mothers.

Women in general were already considered to be second class citizens, confined to low paying jobs or housewife duties. They had been capable of assuming manly duties during the war, but the returning soldiers assumed their place in the workforce and considered it solely their responsibility to support the household. In most cases, a pregnant woman wasn’t allowed to work, let alone an unmarried “slut.” In fact, the self-esteem of any woman was kept at bay by their male counterparts. Only a “stable” couple was considered for adoption, and this was a far better environment for a baby, not in the hands of its rightful mother who had already proven to be irresponsible. Any unmarried mother’s sense of self-esteem was shattered in the process.

Pregnant girls bought into the constant brainwashing, taken advantage of their low self-esteem, to forfeit their babies to a “better” life. After all, it would be “selfish” to not provide your child with this golden opportunity of being raised in a more mature and affluent household. To make matters worse, parents of these young girls were too embarrassed to help them raise these little “bastards.” What would the neighbors think? As a result, babies like me were given up for adoption in exchange for the empty promise of allowing this young girl to return to a “normal” life. It was done, I would imagine, without discussion or resistance in my interest. Years later, I have to admit that I felt it was the only logical and right “choice.” However, no one considered the impact on the mother. This is what the book explores.

A bond is formed at birth that no one can replace. I was given the name Jerry Lee and probably held by her those first few days in the nursery. She was trying hard not to get attached, but after naming her first “legitimate” son the same, I know that she was likely trying to fill a hole. I’m also sure she was further alienated from her family because the “romance” was with a distant cousin, although I believe that he never knew of my existence for this reason and the fact that he went off to war. This, of course, is all speculation because she won’t acknowledge me and he is deceased.

I don’t blame her for wanting to forget my birth, especially after reading this book. She was undoubtedly blamed, shamed, and taunted for her actions that statistically nearly four out of every ten girls her age experienced. Most just didn’t get caught! I was the unarguable evidence that turned out to be good fortune for me but seemingly disastrous results for her; and they say there are no ugly babies. In the process, she unwittingly damaged her family relationships, dropped out of high school, and left home to support herself. She’s since been married twice and lost two children to disease. If she’s like many of the other women in the book, she feels that this misfortune is “punishment” for giving me up at birth. Hopefully, this isn’t the case, but the book shows numerous examples of psychological damage and illness associated with the trauma of relinquishment.

“The Girls Who Went Away” concludes with many heart-warming stories of reunion and healing. Even though I respect her rights of privacy, it makes me even more determined to talk with her. Maybe there’s some relief in knowing I am alive and well? Perhaps, she’s totally blocked out any feeling at all? I did write a letter but have no idea if she received or read it. According to the book sources, the “guilt” of abandoning babies often led to reoccurring nightmares and unexplained maternal discontent or even sickness. Only a reunion resolved these symptoms and led to long-deserved happiness. I’m certainly not conceited enough to believe that I can help her, but I do want her to know that I’m appreciative of what she went through in giving me life. Sadly, it may have been at great cost to her?

Leave a Reply