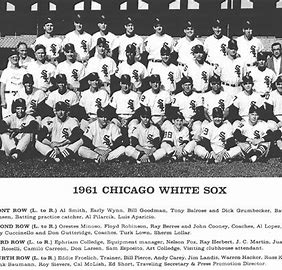

Continued from Post #2619

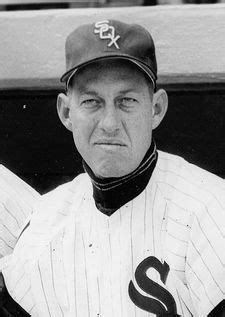

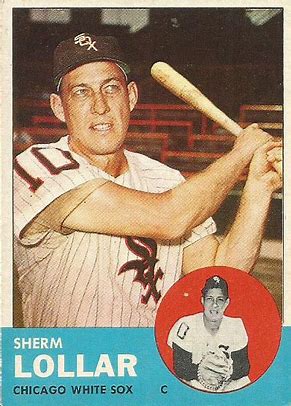

For emphasis, I’m repeating a couple of paragraphs from Post #2616 – Part 7. This is a work in progress, and I’ve tried to keep things in chronological order. However, I keep adding new material every day, and if I do decide to put all this information in book form, I will edit many of the rough edges. I was pleased to note that these articles have moved me up on any website search of the name, Sherm Lollar. I also don’t believe that anyone has compiled this much information on the man, including both stories and collectables. It was just his 100th birthday on August 23rd, so that was the initial inspiration, and the fact that the 2024 White Sox weren’t worth writing about.

After the 1959 AL Pennant, the White Sox were favored by many to return to the World Series. As Roy Terrell pointed out in the April 11, 1960, edition of Sports Illustrated:

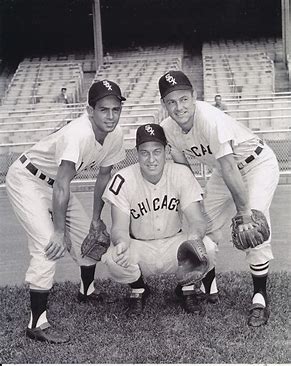

“The White Sox, a gang of quick artists a year ago, are equally quick and artistic and noticeably more muscular. Minnie Minoso has returned, Ted Kluszewski will be available from the beginning, Gene Freese will drive in runs, Billy Pierce no longer has an aching back. Now Roy Sievers, the big slugger from the Senators, has joined the act too. Added to the defensive genius of Sherm Lollar, Fox, Aparicio, and Landis and the pitching skill of Early Wynn and Bob Shaw, this should be enough again to make the Sox again the strongest ball club in the American League.”

Plus, it would have been poetic to win it all, as the 1960 Chicago White Sox season was also their 60th season in the Major Leagues (61st overall).

The Major League Baseball Annual displayed a picture of Sherm with these author comments:

“Loudest noise in the Sox ’59 lineup was made by silent, SHERMAN LOLLAR, the workmanlike catcher. Sherm was high in home runs (22) and RBIs (84) as he registered a not-too-flashy .265 average. Sherm’s booming bat won many late-inning battles, and his smart receiving made the mound staff a bit more effective. Sherm, born in Durham, Ark., started in ’46 as an Indians and went to the Yankees in ’47. There were three seasons past with the old St. Louis Browns before the Pale Hose traded for him in ’52. Sherm’s best of 14 seasons was ’56 when he hit .293.”

So, what exactly happened to the expectations for the 1960 White Sox? I Didn’t have a copy of a 1960 The Sporting News, so I resorted to Wikipedia for some stats. Also, several searches for additional information revealed that media attention had waned from the previous year.

Al Lopez’s opening day lineup against the Kansas City Athletics on 4/19 was listed as: Louis Aparicio at shortstop batting first, second baseman Nellie Fox hitting second, left-fielder Minnie Minoso in the three slot, first baseman, Ted Kluszewski at cleanup, Gene Freese at third hitting fifth, catcher Sherm Lollar following in fifth, Al Smith in right, Jim Landis in center, and the pitcher, Early Wynn. The Sox won 10-9 at Comiskey, but Sherm Lollar was 0-4, an ominous start for him, but a good beginning for the home team. He had moved up in the lineup, not in the traditional catcher’s spot before the pitcher.

An oddity about the 1960 season was that the Pale Hose became the first major sports team to misspell a player’s name, following Bill Veeck’s innovative idea of putting player names on the backs of uniforms. While battling the Yankees in New York, Kluszewski became Kluszewsxi, with a backwards “z.” The Nellie Fox American League record for most consecutive games started at second base ended on September 30, 1960, five years after it started in 1955. Following the season on December 7, 1960, during the American League meeting, Veeck announced that he was interested in selling his White Sox shares with plans of starting an expansion franchise, along with former player Hank Greenberg. Charlie Finley had reportedly offered to buy his shares in the White Sox, but apparently withdrew the offer.

Rumors of a potential sale were swirling even before the season started, made clear in The Sporting News lampooning of Veeck’s “quick draw” history in buying and selling teams. See Post #2518 – Part 9. Obviously, he was counting on another big season for the White Sox, including a World Series title, and a huge return on investment, for once.

In April, the team went 5-4, winning all four games at Comiskey. May was 16-14, with a winning record on the road. June finished 16-13, before the team caught fire in July and went 20-9. August ended 15-15 and September 15-10, followed by 2 October home losses to end the season. Sherm would be hunting and fishing a little earlier this year, while Yogi took his place at the World Series again. When all was said and done, the Sox finished 10 games behind the Yankees and two behind the Orioles.

I did find a blog called, Baseball in the 1960s, written by Bob Brill, who attempts to answer the question of “What Went Wrong?”

“Statistically, the 1960 White Sox were better hitters, stole more bases and were as good on the mound than their 1959 pennant winners. But, instead of first, the club finished third, 10 games back of the Yankees and two back of Baltimore.”

“It can be argued, the Sox, who spent 31 days in first place in 1960 and were in it until the closing weeks of the season, were still pretty good. Maybe it was the Yankees who just got that much better.”

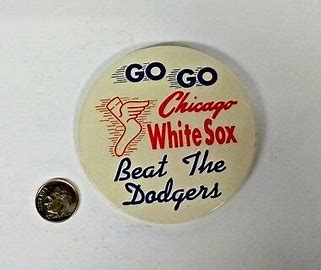

“You might think the ‘Go-Go White Sox’ who ran their way into the 1959 World Series, may not have lost that speed in 1960. When you look at the numbers however, the 1960 club stole more bases 122-113, and scored more runs 741-669 than the previous year. The 1960 club had a better team batting average, .270 to .250, and hit more home runs 112-97.”

“Other key figures show the following. In 1959 the Sox had an on-base percentage of .327. A year later it was .345. Walks were about the same although the 1959 team had 13 more bases on balls during the season – pretty much a wash.”

“Key players in 1960 were Roy Sievers with 28 homers, 93 RBI and .295, and 34 year old Minnie Minoso with 20 dingers, 105 RBI while batting .311. In all five players in 1960 banged at least 10 homers and no one else had more than seven. The previous ‘Go-Go’ season only Sherm Lollar with 22 and Al Smith with 17 had more than nine HR and no one approached 100 RBI. Lollar led the team with 84.”

“Pitching? There are some differences, but were they enough to make the Sox lose seven more games in 1960 than the previous year? The team ERA went from 3.29 to 3.60 which did not help. The home runs allowed were a difference of 2, the walks a difference of 8, but the key indicator, the WHiP went from 1.278 in 1959 to 1.355 in 1960.”

“The starters? Early Wynn a 22 game winner in 1959 with an ERA of 3.17 dropped to 13-12 3.49. Billy Pierce was 14-7 to 14-15 with identical ERA’s of 3.62. Bob Shaw dropped from 18-6 2.69 to 13-13 with a ballooned ERA of 4.06. Reliever Jerry Staley headed up the bullpen both years with amazingly close stats; 116 inning to 115 and ERA from 2.24 to 2.42. The rest of the 1959 pen was somewhat better than the 1960 club.”

“So where did the 1960 club go wrong? A losing streak in June didn’t help. They lost 10 of 14 but even then they still managed to regain first place later in the season.” “

“Maybe the answer lies in the front office. The Sox were an aging team with five of the eight 1959 players in the starting line-up over 30 years old. The team, for whatever reason, chose to trade off several young future stars before the start of the 1960 season.”

“At the end of the 1959 season they picked up Minoso in a deal with the Indians: with Dick Brown, Don Ferrarese and Jake Striker with the Chicago White Sox giving up future sluggers Norm Cash, Bubba Phillips and John Romano. “

“Then they sent a young Johnny Callison to the Phillies for Gene Freese. Days before the season began they opted to send future star catcher Earl Battey to the senators with future slugger Don Mincher and $150,000 for Roy Sievers. The other bungled trade was sending key reliever Barry Latman to the Indians for aging Herb Score. Score would go 5-10 in 1960 for Chicago.”

“It left Sox fans wondering for years what a line up which inlcuded Callison, Mincher, Cash, Minoso and Battey would have looked like? A year later add Pete Ward and they still had steady Nellie Fox with Tom McCraw coming on.”

“And on top of all that; The Yankees got better. New York went from 79 wins to 97 before losing to Pittsburgh in the World Series.”

From <https://www.baseballinthe1960s.com/2019/02/the-1960-white-sox-what-happened.html>

The 1960 White Sox finished 10 games behind the Yankees and two behind Baltimore at 87-67. They were 10-12 against Yogi Berra and the Yankees. Sherm Lollar hit .252 for the season with only 7 homeruns and 46 RBIs in 129 games. He did, however, have two stolen bases.

I guess it just saved us die-hard Sox fans all the disappointment of watching Bill Mazeroski hit the Series winning ninth-inning home run against our team instead of the Yankees.

To be continued…