Continued from Post #2612

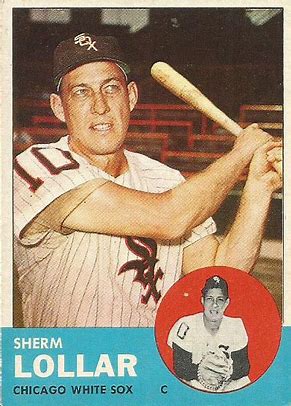

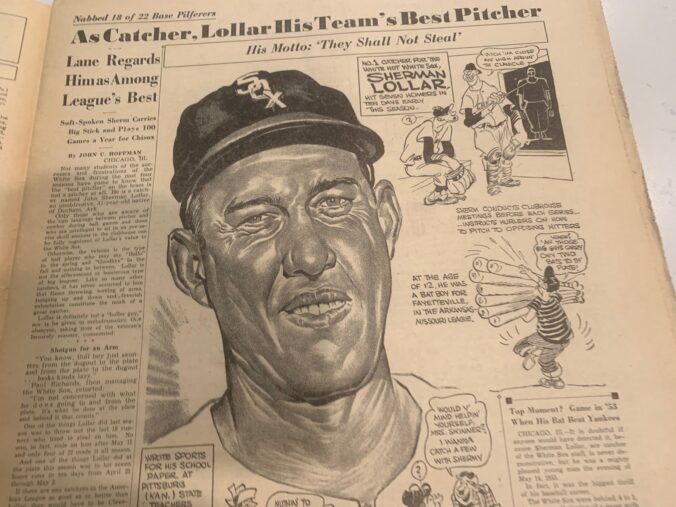

As this series continues, there was another small article by Hoffman on Page 4 of the August 3, 1954, edition of the Sporting News, as he continued to examine the career of Sherm Lollar. The headline read:

At 12-14 Years Battled Priddy, Cooper, and Tucker

“Sherman Loller was in the swing of organized baseball long before he actually became an important part of it. The current number one White Sox catcher was a batboy, warm-up catcher, and batting practice backstop in 1936, 1937, and 1938 for the Fayetteville, Arkansas team in the Arkansas-Missouri League. At the ages of 12,13, and 14, then, he was pleased to mingle with such future Major League stars as Jerry Priddy, Walker Cooper, and Thurman Tucker.

“I was big stuff in those days, Lollar laughed as he recalled his youth. Nothing else would’ve suited me better. Little did I know how far I still had to go to get where I am today, and I suppose there’s still a long way ahead. I hope so anyway.”

According to Wikipedia, Gerald Edward Priddy became a second baseman for the Yankees, Senators, Browns, and Tigers. He was five-years older than Sherm and they just missed crossing paths in St. Louis, since Priddy left in 1949 and Lollar joined the team in 1951. He was groomed to be paired with future Hall of Fame shortstop, Phil Rizzuto, as a double-play combination, after playing together in Norfolk. Priddy was one of the league’s best prospects in 1939, hitting .333 with 24 home runs and 107 RBIs. When it came to playing with the Yankees, however, his cockiness apparently got in the way, with respect to another future Hall of Famer, Joe Gordon. Gordon was the final choice to play with Rizzuto while Priddy was eventually traded to the Washington Senators, where he became a solid starter. Joe Priddy also became a baseball hero to then 11-year-old Maury Wills, just as Sherm Lollar influenced me around that impressionable age.

The second Fayetteville player that made it to the Majors was Thurman Lowell Tucker, six years older than Sherm. A center fielder, Tucker played for nine seasons with the Chicago White Sox and Cleveland Indians. In 701 career games, he recorded a batting average of .255 and accumulated 24 triples, nine home runs, and 179 runs batted in (RBI). Due to his resemblance to the film comedian Joe E. Brown, Tucker was nicknamed “Joe E”.

The third Fayetteville future Major Leaguer was William Walker Cooper. He was 8-years older than Sherm and most likely his closest mentor, particularly since he went on to serve as a catcher from 1940 to 1957, most notably as a member of the St. Louis Cardinals. He won two World Series championships with them and was an eight-time All-Star. After his playing career, he managed the Indianapolis Indians (1958–59) and Dallas-Fort Worth Rangers (1961) of the Triple-A American Association and was a coach for the 1960 Kansas City Athletics, before leaving the game. Cooper is remembered as one of the top catchers in baseball during the 1940s and early 1950s, but like Sherm, apparently not good enough for the Hall of Fame.

It’s time once again for me to get on my soap box when it comes to catchers and the Hall of Fame. As I pointed out in my post titled, Who Was That Masked Man?, a baseball catcher is a special type of athlete. It’s up and down from an uncomfortable squat inning after inning, it’s often guiding and supporting a star pitcher, and it’s being involved in every play. Arguably, no one touches the ball in a game more than the catcher, and no one on the field has a better view of the field of play. They are the field generals and often go on to be managers and coaches. It’s just another reason why these masked men, like Sherm Lollar, deserve more respect from the Baseball Hall of Fame.

As of 2024, there are 346 elected members of the National Baseball Hall of Fame, including 20-catchers, so these “masked men” make up less than 6 percent of these inductees. Pitchers make up the majority, about a third, so catchers that I’ve written about in this series like Lollar, Cooper, Hayes, and Hegan get left out in the cold, even though many consider them to be the best pitchers of all. Baseball is a team game of nine positions, if we don’t yet count the designated hitter. Ask yourself these questions. What would a pitcher be without a catcher? Or the seven other teammates on the field, for that matter? The other half of the battery deserves more attention. Or, maybe just call it the Pitcher’s Hall of Fame?

We don’t judge pitchers based solely on their hitting skills. We judge them on their ability to pitch, so the main criteria for a catcher should be their defensive skills. Although, this is where the game has evolved. Today’s catchers can do it all, and their statistics now make them more competitive with other stars of the game. In simple terms, however, pitchers pitch and catchers catch – that’s the way the game was designed. Let’s give more credit to those who are fundamentally sound behind the plate like Sherm Lollar.

Who’s one of the greatest defensive catchers of all time? Take off your mask Sherm Lollar – with a .992 fielding percentage, a ML record in his era. He also caught a ML record-tying six pop-ups in one game. Look at the statistics chart at the end of this article. It compares the 15 players in the Hall, plus the three “Negro League” inductees and potential inductees, with Lollar’s career. Only Elston Howard, also not in the Hall of Fame, has a higher FP at .993, but he did not play as many years or in as many games as Sherm Lollar. Jorge Pasada ties Lollar, but also played 4 fewer years and 270 less games. He is also not yet in the Hall of Fame. Granted, they were both better hitters, but my point is recognizing the ability to catch and throw out batters. After all, taking away runs from others is equally as important as scoring runs.

Hall of Fame Catchers as of this writing:

Johnny Bench, Cincinnati Reds 1967-1983

Yogi Berra, New York Yankees 1946-1963

Roger Bresnahan: Washington Senators, 1897; Chicago Orphans, 1900; Baltimore Orioles, 1901 – 1902; New York Giants, 1902 – 1908; St. Louis Cardinals, 1909 – 1912; Chicago Cubs, 1913 – 1915.

Roy Campanella: Brooklyn Dodgers, 1948 – 1957.

Gary Carter: Montreal Expos, 1974 – 1984, 1992; New York Mets, 1985 – 1989; San Francisco Giants, 1990; Los Angeles Dodgers, 1991.

Mickey Cochrane: Philadelphia Athletics, 1925 – 1933; Detroit Tigers, 1934 – 1937.

Bill Dickey: New York Yankees, 1928 – 1943, 1946.

Buck Ewing: Troy Trojans, 1880 – 1882; New York Gothams/Giants, 1883 – 1889; New York Giants, 1890 – 1892; Cleveland Spiders, 1893 – 1894; Cincinnati Reds, 1895 – 1897.

Rick Ferrell: St. Louis Browns, 1929 – 1933, 1941 – 1943; Boston Red Sox, 1933 – 1937; Washington Senators, 1937 – 1941, 1944 – 1945, 1947.

Carlton Fisk: Boston Red Sox, 1969, 1971 – 1980; Chicago White Sox, 1981 – 1993.

Josh Gibson: Homestead Grays, 1930 – 1931, 1937 – 1939, 1942 – 1946; Pittsburgh Crawfords, 1932 – 1936; Dragones de Ciudad Trujillo, 1937; Azules de Veracruz, 1940 – 1941.

Gabby Hartnett: Chicago Cubs, 1922 – 1940; New York Giants, 1941.

Ernie Lombardi: Brooklyn Robins, 1931; Cincinnati Reds, 1932 – 1941; Boston Braves, 1942; New York Giants, 1943 – 1947.

Biz Mackey: St. Louis Giants, 1920; Indianapolis ABCs, 1920 – 1922; Hilldale Giants, 1923 – 1931; Philadelphia Stars, 1933 – 1935, 1937; Newark Eagles, 1939 – 1947.

Mike Piazza: Los Angeles Dodgers, 1992 – 1998; Florida Marlins, 1998; New York Mets, 1998 – 2005; San Diego Padres, 2006; Oakland Athletics, 2007.

Ivan Rodriguez: Texas Rangers, 1991 – 2002, 2009; Florida Marlins, 2003; Detroit Tigers, 2004 – 2008; New York Yankees, 2008; Houston Astros, 2009; Washington Nationals, 2010 – 2011.

Louis Santop: Philadelphia Giants, 1911; New York Lincoln Giants, 1912, 1914 – 1916; Brooklyn Royal Giants, 1917 – 1918, 1919; Hilldale Daisies, 1918, 1919 – 1926.

Ray Schalk: Chicago White Sox, 1912 – 1928; New York Giants, 1929.

Ted Simmons: St. Louis Cardinals, 1968 – 1980; Milwaukee Brewers, 1981 – 1985; Atlanta Braves, 1986 – 1988.

Joe Mauer: Minnesota Twins 2004-2018

Catchers likely to be inducted in the Next 10 Years:

Buster Posey: San Francisco Giants eligible 2027.

Yadier Molina: St. Louis Cardinals eligible 2028.

Sherm Lollar was far too quiet and humble to say all this for himself, but he and his contemporaries should be recognized as part of this elite group. He wasn’t flashy and outspoken like the great Yogi Berra. Bottom line, catchers should comprise at least 10% of those in the Hall of Fame.

To Be Continued…