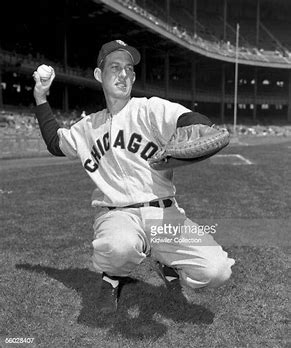

“Now batting for the Chicago White Sox, catcher #10 Sherm Lollar.” Those words meant a lot to me and to probably thousands of other kids my age, as we crowded around the black and white TV set to watch the 1959 World Series. It was a rare treat to watch a baseball game on television. I remember being discouraged, the Dodgers already led the series two games to one, and the Sox were down 4-0 in the top of the 7th when Lollar hit a 3-run homer to tie the score and win my heart.

With the recent announcement and well-deserved induction of catcher Ivan Rodriguez into Baseball’s Hall of Fame, it reminded me how much the responsibilities of that position have evolved through the years. Catchers do so much more than just “catch” in today’s game, and to compare the output of modern day catchers to their predecessor’s decades ago is not a fair assessment of accomplishment. Sherm Lollar was one of the greatest catchers of his era, and deserves Hall of Fame consideration.

A catcher is a special type of athlete. It’s up and down from an uncomfortable squat inning after inning, it’s often guiding and supporting a star pitcher, and it’s being involved in every play. Arguably, no one touches the ball in a game more than the catcher, and no one on the field has a better view of the field of play. They are the field generals and often go on to be managers and coaches. It’s just another reason why these masked men, like Sherm Lollar, deserve more respect from the Baseball Hall of Fame.

As of January 2017, there were 317 Hall of Famers, including 220 former major league players. Other players, managers, and executives have been added to recognize the “Negro Leagues.” Baseball is a team game of nine positions. Mathematically, there should be approximately 25 players per position, 36 if you combine outfielders into a single position. However, with even the addition of Ivan Rodriguez, there are only 15 major league catchers in the Hall (plus 3 from the “Negro Leagues”). I feel this is the first injustice. Ask yourself these questions. What would a pitcher be without a catcher? Or the seven other teammates on the field, for that matter? By comparison, there are 77 pitchers that have been inducted. The other half of the battery deserves more attention. Or, just call it the Pitcher’s Hall of Fame, since they are one out of three players enshrined.

We don’t judge pitchers based solely on their hitting skills. We judge them on their ability to pitch, so the main criteria for a catcher should be their defensive skills. Although, this is where the game has evolved. Today’s catchers can do it all, and their statistics now make them more competitive with other stars of the game. In simple terms, however, pitchers pitch and catchers catch – that’s the way the game was designed. Let’s give more credit to those who are fundamentally sound behind the plate like Sherm Lollar.

Who’s one of the greatest defensive catchers of all time? Take off your mask Sherm Lollar – with a .992 fielding percentage, a ML record in his era. He also caught a ML record-tying six pop-ups in one game. Look at the statistics chart at the end of this article. It compares the 15 players in the Hall, plus the three “Negro League” inductees and potential inductees, with Lollar’s career. Only Elston Howard, also not in the Hall of Fame, has a higher FP at .993, but he did not play as many years or in as many games as Lollar. Jorge Pasada ties Lollar, but also played 4 fewer years and 270 less games. He is also not yet in the Hall of Fame. Granted, they were both better hitters, but my point is recognizing the ability to catch and throw out batters. After all, taking away runs from others is equally as important as scoring runs.

John Sherman Lollar had better stats all around than fellow White Sox Hall of Famer, Ray Schalk, with the sole exception of stolen bases. His timing was unfortunate, since he was overshadowed in his playing days by Yogi Berra in every category but On Base Percentage (OBP). Sherm did somehow manage to get on base despite being very slow afoot. Realistically, however, most Hall of Fame catchers are statistically inferior to Berra, especially in RBIs where he’s the leader of all Hall of Famers at that position. The six-foot-one-inch tall, 185-pound Lollar spent 12 years with the Chicago White Sox and was an excellent receiver who threw out base stealers with regularity (46.18%). He’s ranked seventh on the all-time best list in this category. Only three Hall of Famers were better, including soon to be inducted Ivan Rodriguez. Sherm was a seven-time American League All-Star (nine games), and was considered one of the best catchers and recognized as a team leader during the 1950s. In 1957, he received the first Rawlings Gold Glove Award for the catcher’s position in the major leagues, and went on to earn two more of these awards. His best offensive season was 1959, the year of the World Series runner-up “Go, Go Sox”, in which he hit 22 homers and had 84 RBIs.

Lollar began his career at the age of 18 in 1943, with the then minor league Baltimore Orioles. He was the league MVP in 1945, hitting .364 with 34 home runs. He was then sold to the Cleveland Indians where he made his major league debut on April 20, 1946, but asked to be sent back to the minors so he would have more playing time. On May 8, 1946, wearing uniform #12, he had the honor of catching a complete game victory for Hall of Famer Bob Feller and scored on a Feller sacrifice fly. After the 1946 season, he was traded to the Yankees and wore #26, competing with Yogi Berra for the starting job and ultimately helping the winning effort in the 1947 World Series, going 3 for 4 with two doubles. The Yankee coach, Hall of Fame catcher Bill Dickey, ultimately felt that Berra’s left-handed swing was more suitable for Yankee Stadium than the righty Lollar. Then, a serious hand injury sealed his fate, leading to a 1949 trade to the St Louis Browns. He joined the White Sox in November of 1951 and wore #45 for the first year before claiming #10, a number that I fondly adopted throughout my uneventful Little League and Media League softball years.

After his 18 years as a player that ended on September 7, 1963 with the Sox, his career went full circle, back to the Baltimore Orioles where it started, this time as Bullpen Coach from 1964 to 1968. In 1966, he was part of their World Series Championship season, earning his second ring. He subsequently coached for the Oakland Athletics in 1969 and managed their minor league affiliates, The Iowa Oaks and Tucson Toros in the Seventies.

John Sherman Lollar was born on August 23, 1924 in Durham, Arkansas and died in Springfield, Missouri on September 24, 1977 at 53 years of age. He’s buried in Rivermonte Memorial Gardens. One final baseball honor was bestowed on September 30, 2000 when he was selected to be a member of the Chicago White Sox All-Century Team. He is currently eligible to be identified as a Golden Era ballot candidate when the committee meets again in December 2020.

Sherm Lollar is admittedly my baseball hero. I was never a catcher, but I love the game of baseball and its history. I never had the pleasure to meet him, but when I saw him hit a home run in the 1959 World Series against the Dodgers, he had my attention. I was eight years old and his #10 became my lucky number for life. I have a growing collection of Sherm Lollar baseball cards, so he will always be in my Hall of Fame. He’s one of many players, including other catchers, that have not earned the respect of the Baseball Writer’s and/or Golden Era committee.

I strongly feel there should be more balance by position in the Hall of Fame. I also feel there should be greater emphasis on catching and throwing, when comparing those who excelled as catchers. Sherm Lollar was one of the best at both fielding and throwing runners out from behind the plate. Also, his lifetime .264 batting average exceeds both Ray Shalk and Gary Carter, plus an OPB that outperforms nearly half of Hall catcher inductees. Sherm Lollar is certainly one of several great catchers of all time that should be added to the list of those already enshrined. If not, I’ve made my point and exposed the man behind the mask -my baseball hero – #10.

| Name |

Inducted |

Years played |

Games |

Avg, |

OBP |

SLG |

Hits |

HR |

RBI |

RUNS |

SB |

FP |

RANK/NOTES |

| Mike Piazza |

2016 |

17 |

1912 |

.308 |

.377 |

.545 |

2127 |

427 |

1335 |

1048 |

17 |

.989 |

|

| Johnny Bench |

1989 |

17 |

2158 |

,267 |

.345 |

.476 |

2048 |

389 |

1376 |

1091 |

68 |

.987 |

|

| Yogi Berra |

1972 |

19 |

2120 |

.285 |

.350 |

.482 |

2150 |

358 |

1430 |

1175 |

30 |

.989 |

|

| Roger Bresnahan |

1945 |

17 |

1446 |

.279 |

.386 |

.377 |

1252 |

26 |

530 |

682 |

212 |

.965 |

|

| Roy Campanella |

1969 |

10 |

1215 |

.276 |

.362 |

.500 |

1161 |

242 |

856 |

627 |

25 |

.988 |

|

| Gary Carter |

2003 |

19 |

2296 |

.262 |

.335 |

.439 |

2092 |

324 |

1225 |

1025 |

39 |

.991 |

|

| Mickey Cochrane |

1947 |

13 |

1482 |

.320 |

.419 |

.478 |

1652 |

119 |

832 |

1041 |

64 |

.985 |

|

| Bill Dickey |

1954 |

17 |

1789 |

.313 |

.382 |

.486 |

1969 |

202 |

1209 |

930 |

36 |

.988 |

|

| Buck Ewing |

1939 |

18 |

1315 |

.303 |

.351 |

.456 |

1625 |

71 |

883 |

1129 |

354 |

.934 |

|

| Rick Ferrell |

1984 |

18 |

1806 |

.281 |

.378 |

.363 |

1692 |

28 |

734 |

687 |

29 |

.984 |

|

| Carlton Fisk |

2000 |

24 |

2499 |

.269 |

.343 |

.457 |

2356 |

376 |

1330 |

1276 |

128 |

.987 |

|

| Gabby Hartnett |

1955 |

20 |

1990 |

.297 |

.370 |

.489 |

1912 |

236 |

1179 |

867 |

28 |

.984 |

|

| Ernie Lombardi |

1986 |

17 |

1853 |

.306 |

.358 |

.460 |

1792 |

190 |

990 |

601 |

8 |

.979 |

|

| Ray Schalk |

1955 |

18 |

1762 |

.253 |

.340 |

.316 |

1345 |

11 |

594 |

579 |

177 |

.981 |

|

| Josh Gibson |

1972 |

17 |

|

|

|

|

|

107 |

351 |

|

|

|

Stats not available |

| Biz Mackey |

2003 |

25 |

|

|

|

|

|

40 |

297 |

|

|

|

Stats not available |

| Louis Santop |

2006 |

15 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Stats not available |

| Ivan Rodriguez |

2017 |

19 |

2267 |

.301 |

.339 |

.475 |

2605 |

295 |

1217 |

1253 |

124 |

.991 |

|

| Jorge Posada |

NO |

14 |

1482 |

.277 |

.380 |

.477 |

1379 |

221 |

883 |

762 |

16 |

.992 |

|

| Elston Howard |

NO |

15 |

1605 |

.274 |

.322 |

.427 |

1471 |

167 |

762 |

619 |

9 |

.993 |

|

| Thurman Munson |

NO |

11 |

1423 |

.292 |

.346 |

.410 |

1558 |

113 |

701 |

696 |

48 |

.982 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sherm Lollar

|

NO |

18 |

1752 |

.264 |

.357 |

.402 |

1415 |

155 |

808 |

623 |

20 |

.992 |

|

Bold type indicates #1 in category

Leave a Reply